OK, so. History time!

I’m typing this while in front of a high-resolution monitor. It displays a picture that is 5120 pixels wide and 2880 pixels high, and it can update the screen up to 60 times per second. I don’t really need to know ANY of this, because I plug it into my computer and it “just works”.

This wasn’t always the case, though.

Way back in the day, when dinosaurs roamed the earth, getting your computer to recognize specific monitor resolutions and refresh rates used to be a bit of a pain. There were a few common ones that MOST monitors would support, so connecting your display to your computer would generally give you a picture, but you wouldn’t always get the full capabilities of your display. Like, maybe you’d get a picture at 640×480 or 800×600 but Windows wouldn’t recognize that your monitor was capable of 1280×960.

(For simplicity and sanity’s sake I am going to completely ignore fixed-resolution displays like CGA and just talk about multisync monitors here.)

Anyway, the answer for Windows was usually to install a driver for your monitor. These weren’t really drivers in the sense of code, but more a small text file that explained the capabilities of the display in a way that let Windows adjust. For Linux it was a bit more complicated and involved editing text files in a way that could – in theory – actually damage the monitor if you got them wrong. I never had this happen, and it was probably mostly scaremongering, but it always felt a little risky tinkering with it.

Anyway, this was abject nonsense. In the mid 90s, display manufacturers recognized that it was nonsense and we got the EDID standard, which was a way for displays to communicate their capabilities to the computer so the computer and monitor could hash things out with minimal input from the lump of semi-sentient meat that owned both of them.

I’ve never really understood EDID. It’s been a sort of void, or a black box if you will, that I’ve never been able to see inside of. I’ve just had to accept that it’s there and that it probably works.

Enter my recent experiments with Bazzite and with game streaming, which has honestly worked pretty well. I have two computers that are usable for streaming now, actually – both the original mini PC running Bazzite and a far beefier and far more power-hungry Windows gaming PC.

Neither of these machines have a display connected. Rather, they have little dummy plugs that pretend that a monitor is present, and they do this by presenting EDID data to the computer that describes a monitor. It’s a handy bit of fiction.

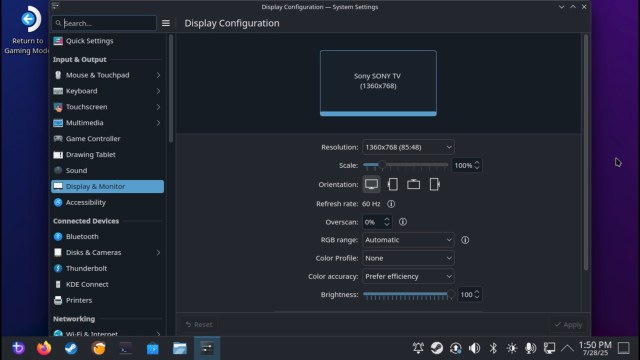

There’s just been one mild frustration with the mini PC. See, it doesn’t have a GPU. It has an AMD APU that delivers stunning CPU numbers but is somewhere around an Xbox 360 or PS3 in terms of what it can do visually. That’s not necessarily BAD, because it plays a ton of really good games, but the issue is that the monitor that the dummy plug pretends is connected is one that can do 1920 x 1080 at 60 hz, and this is a pretty rough resolution for the system to render at. Things are much better when I play games at or around 720p, and most games can be configured for that… but there are some games that see the potential resolution of the monitor and really want to use the higher resolution. It was MUCH better when I had it hooked up to an older Sony flatscreen that only went up to 1360×768. Games wouldn’t try to go above that and the result was a much more pleasant experience.

So, I went looking for a dummy plug that would present itself to the computer as a lower resolution. My ideal solution would have had some sort of way to physically manipulate this, maybe via DIP switches.

I couldn’t find anything of the sort, but I stumbled across this amazing blog post. It was put up like six weeks ago and honestly the timing could not have been better:

I happen to have a Raspberry Pi 3 just hanging around! It was purchased several years ago for a project that failed to materialize, but thankfully I’ve never completely given up on the thought of someday going back to that project. It no longer had an OS installed and in fact didn’t even have a microSD card installed, and there was a minor issue when I realized I didn’t have any spare microSD cards to PUT an OS on… but I eventually stole one out of a digital audio recorder I haven’t been using and got it booted.

Side note: buy some microSD cards so I have them around for the next time.

After getting it up and running, Doug’s tutorial was dead simple to follow. I kept mistyping a variable name, which gave me no end of grief, but things got much better once I realized that I was being held back by a typo and I was eventually able to clone the EDID data from the TV on the new device. I have the EDID data from both backed-up for future use, too – I may someday want to restore the original configuration, after all.

Anyway, plugging the reprogrammed dummy plug into the Bazzite box gave the hoped-for results:

Games now automatically run at the lower resolution rather than trying to push for 1080p, the APU in the mini PC can actually keep up with it, and the overall effect is so much more enjoyable.

His page also introduced me to a site that lets me paste in EDID data and explains it all in a very friendly format. So, like now I know how to read the EDID data from a monitor into a binary file and then look at what the monitor actually has to say about itself. It’s probably not something I will OFTEN need to do, but it’s just very satisfying to see behind the curtains.

Sadly the Raspberry Pi doesn’t have a DisplayPort connector. I have another dummy plug that uses DisplayPort instead of HDMI and I would like to get into its head as well. 🙂